- Home

- Jessica Wragg

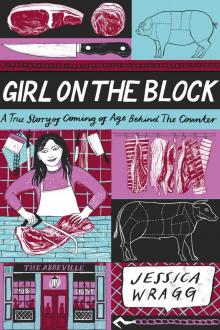

Girl on the Block

Girl on the Block Read online

Dedication

To Mum and Dad, for never letting me down, and for believing this would always happen.

To Hattie and Jamie, for the best seven years of my life.

To Ben, for everything.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

One

Joint Work

Chicken Parcels

Two

Know Your Knives

An Ode to the Women of Meat

Three

The Essential Cuts From Nose to Tail

Four

Primal Cuts

Tying a Butcher’s Knot

Five

A Recipe for Proper Pork Crackling

Rib Eye With Duck Fat Chips, Creamed Spinach for Hattie, and a Salsa Verde for Me

Six

A Field Guide to Rare and Native Breeds

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

I am sitting in the dining room at my grandmother’s house. Her furniture is outdated, still the same as in those blurry photographs of us from the mid-nineties. The table is covered in an old doily, the books on the shelves stacked against VHS tapes. I fell off her yellow sofa at age two, and that same yellow sofa is covered in a thin woolen throw to protect the cushions below.

It is Easter Sunday 2008. We have never eaten lamb at Easter, at least not in my recent memory. My family claim not to be picky eaters, and I suppose that is true, but when it comes to meat, we mostly eat the leaner cuts and we cook them thoroughly. As an only child and only granddaughter who has not once cooked a meal for herself, I eat what I am given, unquestioning. My father and I sit quietly, waiting for the meal. There is a rattle of pots and pans in the kitchen, the hiss of running water, and the low muffled voices of my mama and mother. My granddad died recently.

We are served dinner on china with a brown and red flower trim. I sit, anxious, in what was once my granddad’s chair. This is the first time that one of us has taken his place at the table and I’m afraid of what Mama might think. For a few months after he died we avoided all of his places: his armchair by the window, his chair at the head of the dining room table, the front seat of the silver Ford Fiesta that he used to drive while listening to an out-of-tune radio that was no more than white noise. The first time I sat in his armchair everyone held their breath, and the silence that normally hung over us suddenly felt heavier.

My dad and I murmur thank you as the gravy boat hits the table, clinking against a bottle of fizzy white wine. There are extra wine glasses by our place settings, offset by crumpled cream napkins, and a small bowl filled with strong horseradish that turns my stomach. We say thank you repeatedly, eager for Mama to know that we appreciate her.

Dinner is tenderloin steak, but I’m not sure that anyone welcomes it. On special occasions we are all really craving KFC, which, for some reason, has become a tradition on Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, and sometimes even birthdays. Mum and Mama have bought the tenderloin steak because it is expensive, and there’s comfort in knowing we can afford it. I’m more excited about the McCain oven fries and onion rings that Mama cooks along with the steak and the sweet corn from the tin with its sugary crunch.

The steak swims in hot, pale claret; a gray lump with a little char on the outside in the center of a pallid sea. When I pull on it with my knife and fork, Mum shoots me a look, but I am fascinated. The meat has a feathery grain, and the more I pull, the more liquid oozes out onto my plate—blood mixed with a little melted fat and oil from the pan, wetting the fries until the crispy corners turn soggy. We all say cheers with empty glasses and eat in silence.

The steak goes first on everyone’s plate but mine. I pick over it, and perhaps I look ungrateful, but I am a teenager after all. My first cut reveals blush pink, almost purple flesh, and a thin white strand of something rubbery. It pings back into place when I yank it with the prongs of my fork. Another look from my mother and I slice through the steak and shovel a piece into my mouth. The sinew gets stuck between my two front teeth, and the meat feels dry and heavy on my tongue as I start to chew. My granddad’s heart gave up a few months ago, yet here we are, eating steak.

“Jim’s always does good meat,” says my mother. Jim’s is the butcher shop at the top of Clay Cross, where she and Mama trekked to get the steak the day before. It has been there for years—a mucky white front on the main road running through the small town, outlasting most of the shops and bars that came and went around it. “Surprised he’s still going after all this time.”

“I remember when Jessica was a baby,” says Mama, as if I am not there. She does this often. “We used to take her up to the butcher’s and Jim used to give her a piece of ham. It was before she had any teeth. She used to suck on it and still have it in her mouth when we got back home.”

I look down at what remains on my plate, slice it up, and eat it all, chewing through the gristle until it crunches between my jaws.

One

My mother was the one who had first spotted the job, circling it in red pen and leaving the folded newspaper out on the kitchen table in my full view.

HELP WANTED. VILLAGE FARM SHOP.

CUSTOMER SERVICE ASSISTANTS NEEDED.

REMUNERATION DEPENDENT ON EXPERIENCE.

A week later, I was following a thin, curt woman down white marble steps to her basement office, her mid-heeled, motherly shoes clacking with the weight of her waddle. Gripping the hem of my new yellow dress, bought for me from Topshop because it was of modest length, I tried to look professional as we sat down for the interview. We were surrounded by splintered wooden beams and rubble left in small, neat piles behind red and white caution tape. I wondered if this was where she conducted all of her interviews. In a tiny window high above her head, I could see my mother and father waiting for me under a tree in the courtyard, looking up into the sky at nothing in particular.

In my bag, wedged between the pages of a Vogue magazine to keep it straight, I had my CV, but she did not ask to see it. My cousins, all a little older, had Saturday jobs. One had just bought a car. My best friend worked weekends in a restaurant and something about the way she said “I can’t, I’m working,” like she had inside knowledge of some sweet, secret world, filled me with envy. My friends and I had started to go out on Friday and Saturday nights, and even the occasional Monday or Wednesday. We’d sneak past the bouncers at a cocktail bar up near town center and drink piña coladas until we felt sick, or we’d brazenly drink half pints at the local pub in front of the landlord, who knew full well that we were underage. But at sixteen I was still dependent on my parents, and although they understood where my friends and I were skulking off to, they were generous with my weekly allowance. Suddenly money seemed to be all that mattered because money bought the only things that matter when you’re sixteen—alcohol, tickets to the movies, new clothes. I’d applied and got a call the next day.

The woman and I chatted idly about customer service, and to me, the right answers were all common sense—the bottom line is that you don’t tell the customers to fuck off. She seemed impressed with my responses and assumed that I, like everyone, knew the history of the prestigious farm shop. In a sense, she was right. I’d done a bit of research the night before on our dial-up, while sending doting messages to my boyfriend on Messenger.

The farm shop, famous for afternoon teas overlooking the valley and its array of “fancy” food, was perched in the hills of the Peak District and surrounded by fields of plump Jersey cattle. We had driven through the estate, home to a duke and duchess with a long-standing family history, to get ther

e. The long, sharply winding road cut through acres of plush green countryside, deer scattering as my dad floored the accelerator—God forbid we were late. Herds of sheep grazed manically down by a river stretching miles into the distance. The house itself—after which the estate, the farm shop, even the yearly country fair were all named—sat happily halfway up a steady hill and had done for six centuries. One of the most famous surviving country houses in the world—five floors, one hundred twenty rooms, gilded windows—the house is mentioned in Pride and Prejudice, and it was used to film the accompanying period drama in the early 2000s. You know the one, with Keira Knightley pouting her way through a two-hour adaption that turns out not to be a patch on the BBC version.

The farm shop itself, though not nearly as grand as the house, was still pretty. It was essentially a glorified bungalow: an L-shaped single-story building with blue-framed windows and a thatched roof. Outside stood fruit stands with wicker baskets piled high with apples and oranges, papaya and watermelons. Ivy twisted around the brickwork of the entrance and over an automated sliding door—a more recent addition to the structure. Upon entering, customers were greeted by a table of seasonal trinkets: on the day of my interview, picnic hampers and checked blankets. Toward the back of the store was the fish counter, the butchery, and a huge bakery that immediately caught my eye due to the sheer number of carbohydrates on display. Wooden shelves were stacked with jams and pickles and bread and cakes beneath warm yellow lighting, every item plastered with a label that bore the farm shop logo: a line drawing of the house’s pastoral façade.

The customers milling around the shop floor were dressed to the nines: women in high heels, flowing dresses, and tight skirts, men in their best dress shirts and jeans. I wondered aloud if there was an event that day, but my mother, with a snide tone, said that they were all probably hoping to see the duke and duchess on their weekly shop. “We only come here for a treat,” she continued, “when your dad wants some posh naan bread or I want a nice bit of stewing beef.” I didn’t have the heart to tell her that I didn’t know the difference between “nice” and “not nice.”

We were early for my interview and spent ten minutes wandering around, picking things up from their shelves and putting them straight back down again when we saw the price. There was so much that I’d never imagined needing, and yet I couldn’t help but feel that now I needed it all: seeded ciabatta rolls with sun-dried tomatoes mixed into the dough; fifty different kinds of cheeses, all behind spotless glass and ready to be cut by hand; exotic bottled beers with their beautiful, bright labels, suddenly making my throat dry up with an intense thirst.

I relayed what I knew of the shop’s history to the woman, working from the imagination that had done me so well in the past. She listened with a wry smile. It clearly wasn’t enough, but she commended me for my effort and continued on with her own rehearsed spiel, a proud little smirk flickering in the corner of her mouth.

“Yes, and all of that is true. But, to give you a brief background, the farm shop was opened by the dowager duchess in the late 1970s, mainly to sell beef from the cattle reared on her estate. Almost forty years later, the farm shop remains one of the first in Britain and one of the oldest. Any questions?”

I shook my head. I’d read somewhere that the best thing to do in an interview is to look interested and keen and wide-eyed, and to ask questions, but at that moment I couldn’t think of a single thing to ask. I looked on as she obsessively combed through her brittle curls with long fingernails and made notes in a scrawled hand. When she had finished writing, her small eyes flickered to the roster on the facing wall, and we began to discuss pay: six pounds and twenty pence an hour. That sounded to me like a fortune.

“Weekend work—Saturday and Sunday—does that sound fine to you?”

I nodded. “Yes, I go to school on weekdays.”

She seemed not to care if I went to school or not.

“Now,” she said, crossing her arms. This, it was clear, was important. “I’ll explain your options, and you can number your preferences, one being the most preferable and three the least.”

I nodded.

“We have the deli, or the delicatessen, the fishmonger, the butchery, and the till section. Which do you like the sound of?”

I shook my head. “I really don’t mind.”

She consulted the roster once again and cleared her throat softly in a way that only upper-class people do. She was clearly annoyed by my ambivalence.

“Right, well. Let’s start you with the butcher’s.”

“THE BUTCHER’S?”

We were in the car on the way home, careening down narrow countryside roads with Dad behind the wheel. In all of five minutes, once I’d told them the details, Mum and Dad’s excitement about my upcoming “trial shift” had given way to skepticism.

“Do you know anything about meat?”

I didn’t, but I could learn. I could see Mum’s eyebrows furrowed in the rearview mirror. Their concerns were practical, and they liked to imagine the worst-case scenario first. In their minds, the farm shop expected me to pick up a knife and know how to cut up a cow straightaway. They assumed I’d probably give it up within the first week.

As a general rule, my family did not buy our meat from a butcher, and nobody we knew did either. My hometown of Chesterfield had struggled with recession and a spiraling economy; once a historic market town boasting a church with a famously crooked spire, Chesterfield was now best known for its namesake brand of cigarettes. We weren’t foodies, and we didn’t see the point of spending a lot of money on food. My mother had a handful of meals that she rotated weekly, and if we went out to eat, it was typically to the Greyhound Pub a mile away for a chain menu of rotisserie chicken or to Frankie & Benny’s for ribs and fries.

Our meat, besides on special occasions, came from the supermarket, from Morrisons and Tesco in plastic trays. We rarely ate anything other than chicken, and sometimes beef casserole on Sundays when my dad would get up earlier than everyone else to put turnips and rutabagas in the slow cooker. At sixteen, I had little interest in the provenance of my food. The farm shop seemed like a completely foreign world, but it was one that would pay me minimum wage on a fortnightly basis.

“They’ll just have me serving customers, Mum,” I said. “Customer service assistant. That’s what they’ve hired me for.”

“Well, a job is a job,” said my dad, and I heard his underlying tone; he was talking about money, having an income, not bleeding them dry for clothes and nights out with friends. My parents had sacrificed a lot for me, and who knows how much money I’d sponged from them over the years. Mum had stopped working when I was born to take care of me, and Dad worked for a construction firm managing plant vehicles. He rarely left for work later than five in the morning and came home every evening after six.

“You’ll have to touch the meat, you know?” said Mum. “Are you going to be alright with that?”

“Just meat, innit?” I replied, annoyed at their pessimism. I didn’t want to talk about it anymore. In my mind, I was newly employed and had already planned out what to buy with my first paycheck.

They were certain that I would hate the job, but at the same time they knew their daughter—competitive and usually too stubborn to admit defeat. This often had me in difficult situations. There was the time I’d tried to learn “Für Elise” on my keyboard and had driven them both insane by playing for hours, starting the song again whenever I inevitably made a mistake. Then there was the time when I forced them to throw a Halloween party in our garage and decided to decorate the whole room ceiling to floor with black trash bags split in half. We were peeling bits off the walls for weeks. If they showed any uncertainty about something I’d said I was going to do, it only spurred me on to try twice as hard. This job was no exception.

I FELT INVISIBLE AS I CROSSED THE THRESHOLD OF THE FARM SHOP on my first day, weaving through a sea of customers and the fresh fruit and veg at the front of the shop. On Mum’s recommenda

tion I’d gone light on makeup, applying only a smidgen of Maybelline Dream Matte Mousse and thick black eyeliner, and I’d straightened my hair to within an inch of its life. The butcher’s counter, all the way at the back of the shop, occupied the biggest space of any of the departments. The glass case of the meat counter was probably twenty-five feet long and it fit like a puzzle piece into the rectangular space it had been allocated. As I approached, I saw staff in blue aprons and white mesh hats serving customers from behind the counter, and then I peered even farther through the glass that separated the counter from the cutting room and the fridges. Six large men were working behind that glass, some of them short but still hulking with muscles beneath their white overcoats. Their heads were down, eyes hidden beneath the brims of their hats, the silver blades of their knives glinting in the overhead lights, left hands covered with thick metal gloves, which I discovered later were chain mail.

Behind the counter, to my right, were two silver machines, chrome steel spattered in specks of blood and creamed fat. A counter boy who looked about my age flitted between a wooden cutting block and an impressive gray till that seemed too modern for the rest of the setting. When he had finished serving the customers who were waiting, he pressed a button that emitted a shrill, loud beep. Above his head a red digital number moved from 70 to 71. There was no customer 71. I was the only person who stood in front of him. He took one look at me and deduced it all, checking the clock behind him.

“New girl?”

I nodded.

He gave me another long look, his eyes narrowing, and then with a slight nod of his head motioned for me to come around behind the counter. I stepped from the terra-cotta tile of the shop floor up onto gray grip linoleum and followed him back. All six of the men in white coats stopped their work as we got closer and began to sharpen their knives. No one spoke. The only sounds were the fridges humming at a low frequency, the clomp of the boy’s boots on the floor, the swish of knife on rough steel, and the crackle of an old battered radio struggling for signal.

Girl on the Block

Girl on the Block