- Home

- Jessica Wragg

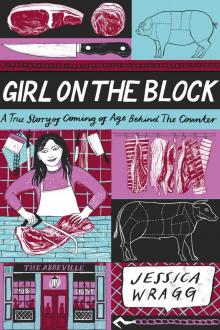

Girl on the Block Page 10

Girl on the Block Read online

Page 10

Flavor is subjective, that’s something I’ve always understood. At first, the flavor was so strong that I wondered if something had gone wrong in the cooking process. It was unlike any beef I’d tasted in my life, so different from the overcooked tenderloin at my parents’ house, the braised beef we used to serve on Sundays, or the cremated aitch bone joint that my Nana used to cook and slice for us every weekend. Still moist, with blood seeping from the cooked muscle, this steak was fatty, unctuous, rich in flavor. The only way to describe it was that it tasted like beef.

The steak was thirty-five days aged, which by the standards of many butchers, is nothing at all. There are butchers around the UK and around the world who age beef for a minimum of forty days, and there are those who take it to the extreme and go to one hundred or one hundred and fifty days. The older the steak gets, the more concentrated the flavor becomes. I find that anything aged longer then forty-five days tastes less like steak and more like an aged, ripened cheese.

The science behind dry-aging is something that continues to fascinate me, although the concept itself is pretty simple. Like humans, cattle are made up mostly of water. A carcass of beef will be around about 75 percent water when it’s at dead weight. Dry-aging aims to get rid of a small percentage of that water in order to intensify the flavor and increase the tenderness of the meat.

The dry-aging process begins when a bullock or heifer is slaughtered and cut into primals, smaller cuts from a whole carcass like a top bit (top of the leg), roasting (muscles that run down the back), and chuck (the shoulder). Butchers may or may not choose to break these primal cuts down further into sub-primals, such as rib, short loin with the porterhouse attached, or sirloin. At this point, most of the beef destined for a supermarket is removed from the bone and shrink-wrapped for wet-aging (which we’ll come to a bit later). To dry-age, the joints are put on a shelf in a fridge with a temperature somewhere between 32 and 39°F (0 and 4°C) and a humidity level somewhere around 80 percent. And that’s all there is to it; the cut is then left for a number of days to allow moisture to leave the beef via osmosis and the outside of the beef to grow mold.

After days one to five, the beef will appear sticky and wet on its outer surfaces as the water makes its way out of the meat, into the air around us, and molding begins. The fat will remain dry, as it contains less water and is therefore the last thing to mold. After days five to fifteen, this wetness will reduce, causing the outer surfaces only to darken and begin to form a thin, hard, red crust. After fourteen or fifteen days, many butchers will stop the process. With the loss of water comes the loss of weight, and therefore their profit margins will be decreased. The mold will begin to make its way into the inner muscles of the piece of meat itself and will have to be trimmed out or, even worse, wasted. Less meat to sell, less meat to put on the scale, and less cash handed over by the consumer.

But there are the daring few who continue this process. According to experts, once beef has been aged more than twenty-eight days, it peaks in terms of flavor and tenderness, though this is still considered to be young by many of us. By day fourteen to twenty-one, that red crust begins to thicken on the outside, turning a darker, deeper maroon color. The fat and marbling inside the meat will, rather unpleasantly, turn gray as the mold begins to work its way past the outer surfaces. Days twenty-one to twenty-eight, the surface will turn black and completely hard. At thirty-five to forty days, the meat itself becomes stiff, making it much more difficult for butchers to break down, but you have just about the perfect, beefy flavor.

According to a 2013 report on dry-aging by food writer Francis Lam in Bon Appétit, dry-aged beef, on average, costs the US consumer double that of a wet-aged piece of steak in a restaurant. In a UK butcher shop, you’d be looking at about a third of the price added on to a raw cut over the counter. Is it worth it? I’m biased, but even knowing all that I do, I have to say yes. Wet-aged beef, although technically easier to produce, lacks a real depth of flavor compared to its dry cousin. Supermarkets and larger meat merchants tend to prefer this method simply because when meat is sealed in a vacuum pouch, there is almost no loss of moisture or weight in the cut. This increases their yield and therefore their profit margin, and they can leave a sirloin or rib eye in a vacuum bag on a shelf for up to twenty-one days before selling it. Watch out for this when shopping for steaks—a piece of meat that has a 21 DAY AGED sticker on it hasn’t necessarily been dry-aged and is unlikely to be packed with any real flavor.

The Ginger Pig operated in ways I had never dreamed possible. When beef deliveries would come in on Tuesdays, Thursdays, or Saturdays, some of it would be bright red and fresh, killed just the day before delivery. Other pieces would have already been hanging for four weeks at the company’s main butchery in Yorkshire before they arrived, the fat gray and the outer surfaces black, and once broken down yielding the deepest and most delicious maroon hue with a pungent smell unlike any other. The meat at GP wasn’t cheap, that’s for sure—almost fifty pounds per kilogram for tenderloin and anywhere upward of ten pounds per kilo for ground beef—but they had their demographic nailed. We served footballers and their wives, and actors and actresses that I’d seen on television. Nigella Lawson was a regular, and I’d even once, in a fit of embarrassment and excitement, given Eddie Redmayne a hefty discount despite the fact he could absolutely afford the tenderloin tails he bought. People were prepared to pay good money for good meat reared properly and taken care of. The more I latched on to Erika and the more I read up on dry-aging and procurement and slaughter online, the more determined I was to learn. I was certain that the only thing holding me back was that the environment was wrong, and so after six months in Marylebone, I requested a transfer to Borough Market. That change was granted.

Working at the market was terrifying at first—I was the new face, and the shoppers saw that straightaway. In Marylebone, I’d developed relationships with the people we served, but at Borough Market certain customers were hesitant to trust the “new girl” and some would even wait their turn only to request to be served by someone different. These were mainly the other market workers, used to familiar faces and the discounts they brought to them. Ten, even twenty percent was the going rate, and this was reciprocated by fishmongers, cheesemongers, and hot food stalls throughout the entire market. It took a good few months for me to be recognized, but eventually I began to leave work with bags of fresh mussels, gooey brownies, and charcuterie that, if I haggled hard enough, could be bought for the same price as I might pay at the local Tesco.

My flatmates were elated, and soon it was a case of “If you’re at the shop today, could you bring me back a couple of sausage rolls or some chicken for lunch?” or “Could you nip around to Neal’s Yard Dairy and get me a lump of cheddar?” or “Any chance of some fish for the grill later?” Being recognized as a “Pig” by the market traders came with a deep sense of community and pride that just hadn’t existed in Marylebone. The closest I’d gotten to that there was a free banana from the lady who worked weekends at Waitrose on the checkout.

Thankfully there was also a friendly and familiar face behind the counter in Borough. Kyle had worked with me in my first few months at Marylebone. Almost thirty, with a terrible smoking habit that only enhanced his dirty cockney accent, Kyle was kind to me, and naturally I started to develop a crush on him. Never mind that he was ten years my senior and a video game nerd of the highest degree.

Along with the other butchers in the market, we would often go out for drinks after work or bring pints into the shop after hours from the oyster house across the road. Often our chats involved nothing other than work, football (for the guys, mainly an Arsenal vs. Tottenham debate that on a couple of occasions almost turned physical), and smoking profusely through the iron gates that locked up at night. I’d always change into a nice outfit for these occasions, hoping that Kyle might notice, but I don’t think he ever did. Finally, at a company Christmas meal involving plenty of booze and lots of laughter, Kyle and I had a

real talk. He said that at thirty, he wanted his next girlfriend to be the person he ended up with for life, and he didn’t see that person being me. The following week, the entire company seemed to have learned about my feelings for Kyle and had taken to giving me a light ribbing whenever they could. I began avoiding him at all costs. We drifted apart, and he left a few months later to move to Canada to live with a woman he’d met on the internet. They have a son together now, so I guess he really did stick by his word.

At the farm shop, Christmas hadn’t been a big ordeal and was mostly enjoyable. The other customer service assistants and I would go in early on the twenty-second and the twenty-third to help run holiday orders, of which there were hundreds, with a queue of customers that snaked halfway around the perimeter of the store. The butchers were always tired at this time of year, but we never thought to ask how many extra hours they’d worked. We all looked forward to Christmas Eve at the shop, when as our reward for all the hard work we’d put in that year, we got to gorge ourselves on mimosas and bacon sandwiches. The manager made his rounds and thanked us all in his ridiculous accent, so alien to our own broad and harsh Northern tones. He sounded much like a BBC newscaster from the 1950s. At one o’clock, the shop would close and after a hefty and quick clean-down, the entire staff would traipse down the often snowy tracks to the pub in the village for drinks and chip sandwiches. Everyone would leave suitably drunk and ridiculously full and, depending on their hours, might not be in again until the New Year.

At the Ginger Pig, Christmas caught me off guard. With my family still back in Derbyshire, I’d naively expected to work my usual Saturday and Sunday shifts before being collected by my dad, who would drive all the way down to London to fetch me each year, back in time for a couple of days’ rest before the big day. I was scheduled to work in Marylebone to help with their extra Christmas business, but it was only after speaking with Piotr that I realized the severity of what I’d signed up for. There were talks of one-in-the-morning finishes, whispers of twenty-hour shifts, horror stories of a four-o’clock close on Christmas Eve, and then a hefty clean-down, which would see us leaving for home at six in the evening. Having finished my semester at university almost half a month prior, I was ready to go home for some time with my family and to catch up over drinks with my Chesterfield friends. I panicked, and I’ll be the first to admit that this wasn’t my finest hour: I made up a complete lie to avoid the Christmas mayhem. I told Piotr that my grandma was on her deathbed, that she might not see Christmas through, and that I had to go home on the twenty-first and wouldn’t be back in London until the New Year. Selfish, horrible, despicable, I know. Both my grandmothers were perfectly fine. But I was twenty, and I was eager to get home. Looking back, I’m both pleased and disgusted that I pulled it off.

Afterward I remember spending an entire afternoon on the bacon slicer as the orders flooded in, cutting what must have been three hundred kilos of smoked belly bacon into thin strips and laying them as neatly as I could into a skip with a blue liner. We had been taking Christmas orders for weeks, and now in December we’d reached critical mass. I watched the black-and-white Brother printer struggle to churn out five hundred order sheets, secretly thankful that I wouldn’t have to be there when the holiday madness reached a fever pitch.

That was only my first Christmas at the Ginger Pig. After four more there that I didn’t manage to avoid, I have come to hate the holiday. Yes, retail is foul, and I know that emergency service work is no mean feat. But imagine pulling the guts out of a French guinea hen at three thirty in the morning on Christmas Eve after being at work since five the morning before.

Five of the Christmases I’ve worked over ten years as a butcher have proven to be hundred-hour weeks. The longest Christmas shift I ever pulled was twenty-three hours, with a one-hour rest before getting up to go into work again. I’ve known managers who worked forty-eight hours straight without stopping, and one of my good friends at the Ginger Pig nailed a seventy-two-hour no-resting, no-showering shift in the three days running up to Christmas. The tips are good at this time of year, but overtime pay is unheard of. At the end of the week, when you finally get that sweet paycheck just before New Year’s, you’re left with nothing like the figures you’d dreamed of once the taxman has taken his share.

A good percentage of London trusted their most important meal of the year to us, leaving things in what they knew (or believed) were our capable and caring hands. Although each Christmas order is cut and packed by hand, those capable hands might belong to a butcher who is running on two hours of sleep and has been working for ten days straight. On the lead-up to Christmas, a butcher’s schedule might look something like this:

DECEMBER 12TH TO 16TH This is the most enjoyable and relaxing part of the Christmas period for me, with my social diary jam-packed. It’s normal working hours for us at the shop, nine-hour days and we close the shop at the civilized hour of five or six in the evening. This is our last chance to see our friends and family before the madness sets in, so there’s plenty of booze and early present swapping. I like to wander through the Christmas lights on Regent Street and get my present shopping done.

DECEMBER 17TH TO 20TH Christmas orders close on the 17th, and then it’s time to relay to our suppliers exactly how many turkeys we’ll need from them. Most Brits will devour a turkey at Christmas, although the traditionalists still enjoy a goose or a duck, which was part of British heritage until we adopted the American turkey trend in the late nineteenth century. Most years we’ll also bone and roll around fifty ribs of beef, prepare around one hundred bone-in rib orders, take in thirty or forty sides of pork to one shop to be broken down, and spend entire days on end just working on one type of meat before vacuum packing so that it keeps fresh for the big day.

DECEMBER 21ST This is when the fun begins. We start handing out Christmas orders to the masses, and orders for the 22nd and sometimes the 23rd need to be prepped, all while the shop is still open for regular business. We bring in extra staff, but this is barely a help, as butchers are needed for the cutting work away from the counter to prepare for the days coming. When the shop closes—still regular hours, so around six o’clock in the evening—we’ll prep around 150 orders for the 22nd of December.

DECEMBER 22ND This is the worst day for many of us. Most customers don’t want to risk picking up their roasts on Christmas Eve, instead opting for pickup on the 23rd, so we spend the 22nd preparing. Christmas 2018 was a soft one for me, the longest day at only nineteen hours. When the shop closes at around six thirty, we’ll order pizzas in their tens and prep orders late into the night, taking frequent smoke breaks. This is the shift we all dread; we’ll get around three hours of sleep before waking up to begin work again the next day.

DECEMBER 23RD This is usually a shorter trading day, with around two hundred orders that have to be packed for pickup between eight in the morning and two in the afternoon. We’ll finish up a little quicker, though, as the 22nd helped us to get into a rhythm of cutting, packing, and hanging up orders. Everyone is shattered; bags are starting to show under our eyes and we’re lucky if we remember to put on deodorant, let alone makeup. Our feet are blistering in our steel-toed boots in places we don’t even understand, commonly beneath the toes and on top of the foot where the laces tie. Most of us have been wearing the same work clothes since we started the run. My jeans, by this point, are covered in dried beef fat and the crusted slime of chicken.

DECEMBER 24TH The race is almost over. Most of us will come in on Christmas Eve with a renewed sense of purpose, knowing that we have only ten hours to go until close. The 24th is an odd day. Often there will be a queue of a hundred customers snaking around the block, waiting eagerly for the shop to open at eight o’clock in the morning. They want to be let in, to get their dinners and go before the rush turns bad. Around a hundred boxed orders will be stacked in the shop, each with number and a surname. We’ll fish them out of the pile in turn when each customer walks into the shop with their receipt. There�

��s always someone who comes in without preordering, on the off chance of finding an available bird for their table. This person will walk away with a seven-kilo bird to feed a family of four. When the shop closes at two, we call those who haven’t come to collect their orders, and if they don’t answer, their Christmas dinner is unfortunately ruined and we keep the stock in the fridges until we open again on the 27th. At three o’clock, the clean-down is almost finished, the tips are counted, and we’re free to go, to collapse at home with a pint or five, and enjoy our families.

Before I became a butcher, Christmas Eve meant going out with friends or enjoying a meal with my family. Now it usually ends with me falling asleep in the bath at my parents’ house, trying to soak away the stench of meat at six o’clock in the evening. It’s just as well, as Christmas with my family was never all that active anyway. Christmas Day is simply a Sunday roast with an exchange of presents before, and it’s just the four of us—Mum, Dad, Mama, and me—since Granddad passed away. Usually the dinner that took Mum four hours to prepare is finished in ten minutes. We drink a lot, we always do, with my mother having bought a bottle of my favorite gin and a fancy tonic to enjoy in the evening after Mama has left us to settle down. Then Dad will fall asleep watching a rerun of the British classic comedy Morecambe and Wise, and I’ll play with the new makeup I’ve received or try on the new clothes from Mum before I fall asleep. The week before takes so much out of me that I’ll sleep twelve or thirteen hours a night while I’m home, see a couple of friends, and spend the remaining Christmas holiday in front of the television on a Netflix binge. Boxing Day is chaotic—spent with the Wragg side of my family who all have given birth to plenty of children who, during present giving, tend to get wrapping paper in places you’d never have thought possible. My favorite day is the 27th, when every year Mum, Dad, and I go to Liverpool to do some shopping and wander around the Beatles museums. It feels as it should—the three of us laughing and joking and singing along to Paul McCartney tribute acts in the basement of the infamous Cavern Club. I’m usually back to work for the 28th or 29th.

Girl on the Block

Girl on the Block