- Home

- Jessica Wragg

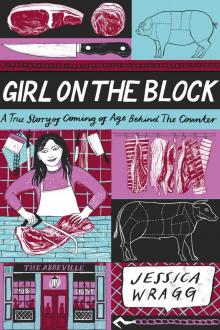

Girl on the Block Page 15

Girl on the Block Read online

Page 15

My eventual schedule was Tuesday through Friday in the offices with Will, and then Saturdays down on Oxford Street, waking up at five in the morning to get down there in time for a six thirty start. Toward the end of a shift, I would finish up work at the counter as early as I could manage, change my clothes, and rather pathetically try to wash in the staff toilet sinks before leaving through the back exit. After a quick cigarette, now off the clock, I would reenter the store as a customer, wander around the designer shoe hall, ogle the perfumes, and sometimes buy something from the high street section. Then I would leave again through the customer entrance to walk down the length of the store on Oxford Street, looking at the window displays, which were always spectacular. This was the only way I could cope with the horror of working inside.

A kind of nonsensical language used among butchers to fool customers known as backslang became essential behind the department store counter. I’d heard a lot of backslang during my time in Borough Market from Kyle, who taught me the basic words and enjoyed using those that I didn’t yet understand when I was around. The use of backslang among butchers dates back to Victorian times, and it’s essentially the art of speaking a word either backward or out of order. It originated among Smithfield traders in the mid-nineteenth century as a way to openly discuss the price, quality, and age of meat in front of customers, and it eventually became a way of discreetly insulting or commenting on a customer’s appearance as well. Backslang became so prevalent on London’s East End that it eventually gave way to cockney rhyming slang, a form of slang that replaces a common word with a phrase of two or more alternate words, the last of which rhymes (for example, “butcher’s hook” is rhyming slang for “look”).

The rules of backslang are simple—in most cases, the last letter of a standard word becomes its first syllable. Some words, however, proved harder than others to reverse, and so butchers developed their own way of making them clearer. Some old-school butchers can have entire conversations in backslang, which makes my head spin. Modern backslang rests on a core vocabulary that comes from our Victorian predecessors, and it’s rare to find a new term thought up by someone in the twenty-first century. Some examples:

EL-RIG The backslang for girl. From experience, el-rig is most commonly used in conjunction with tee-serbs (breasts), s-gel (legs—pronounced ess-gell), and y-naff (vagina—pronounced why-naff). Mostly used to discuss a woman’s physical attributes without being accused of ogling. S-gel and tee-serbs can also be used to talk about cuts of meat from lamb, chicken, and pork.

GAF Meaning fag, for cigarette. Used by butchers, including myself, when it’s time for a cigarette break.

TISH Although not technically spelled backward, tish is backslang for shit. Most commonly used when the quality of meat is poor or when a butcher is nearing the need for a toilet.

DLO Prounced dee-low, this means old and might be the most useful piece of backslang you’ll ever learn as a customer. Listen for it if you’re buying meat in a butcher shop, as often dlo is used to push the older pieces of meat for sale and save the fresher ones for longer.

KAY-ROP, BEE-MAL, FEEB Backslang for pork, lamb, and beef; another good few words to listen out for in case of foul play behind the counter.

Backslang in the department store was essential, because we could let each other know, very simply and clearly but without a customer realizing, that a piece of beef at the back of the tray was old and was to go first, that someone needed to go for a cigarette, or that we thought the floor manager was a cunt. Sometimes the butchers would use backslang to discuss women walking by, although I tried hard not to listen and to scold them when they did it. I found it unsettling, but I’d heard it before in the market, and it was easy to let slide, as it happened so much and seemed like part of the culture. David, who would do anything to be taken more seriously as a butcher, went out of his way to speak in backslang, even when it wasn’t needed: at drinks after work or in a casual conversation that had nothing to do with the meat we were cutting. Although I yearned for a “grown-up” job and loathed the disorganization of the department store meat counter, using backslang with the other butchers there often made me feel like I was back where I belonged behind the block.

A Recipe for Proper Pork Crackling

Pork crackling, when served alongside a Sunday roast at my house, is always the first thing to go. There’s something about the unctuous saltiness, the almost tooth-shattering crunch, and the explosion of the rendered fat on your tongue that makes it the most treasured part of the meal. This, unfortunately, also means that when crackling is done badly, it’s the worst kind of disappointment.

Proper crackling is easy enough, but there are certain elements you’ll need to control to make sure that it comes out perfect. Too much moisture in the skin itself and you won’t get the crispiness desired, too much fat beneath the skin and it will render too much and undo any work the oven has done before you.

Crackling, I’ve found, is best cooked in one larger piece first and then shattered into smaller pieces afterward. Ask your butcher for extra pork skin, and he or she may have to order it in for you specially (crackling is so popular in the UK that leftover pork skin is often in short supply).

The skin you buy should be firm and tan in color with just under an inch of fat beneath, and that’s normally down to high-welfare rearing, as the animals will have been allowed to lay down fat gradually. Some butchers will sell pork with thin, floppy pale skin. This barely ever has enough fat on the underside and is a surefire sign of low-welfare rearing—the paleness in the skin itself is a giveaway of no light or sunshine and a poor diet.

You’ll need a piece that’s about 10 by 7 inches. Ask your butcher to fine score the skin in lines, not in crisscross, as at the end you want strips, not diamonds. It should be scored finely, to let as much moisture evaporate as possible. Then ask your butcher to cut it into strips approximately ¾ inch wide.

Rub a good handful of coarse sea salt into the scoring of the skin. Shake off any excess and leave the skin outside the fridge for 15 minutes while you preheat the oven to 425°F (220°C).

With a dry kitchen towel, pat off any moisture that the salt has brought out of the skin. In a small bowl, mix sea salt, crushed fennel, black pepper, and garlic powder in a ratio of 4 parts salt to 1 part everything else. Massage the salt mixture into the skin, being careful to get right in between the score lines.

Once your oven has preheated, place the skin on a baking sheet and bake for 20 to 25 minutes. It should crisp and bubble, with the fat beneath rendering off into the pan below. As necessary, pour off some of the pork fat into a pitcher (when cooled, it makes a great fat to baste potatoes with) and place the skin back in the oven.

When finished, the skin should be light and deep golden, the fat almost rendered, and very crispy, a little like puff pastry. Allow it to cool before breaking it into smaller pieces, if so desired.

Serve with applesauce for dipping or alongside a roast dinner.

Rib Eye With Duck Fat Chips, Creamed Spinach for Hattie, and a Salsa Verde for Me

The trick to this recipe is to prep. In all my cooking, I tend to do as much of the prep as I can beforehand so that I’m not left doing three things at once. With steak, especially, this is essential. You want the majority of your attention focused on the meat and not on anything else. Contrary to popular belief, it’s almost always better to prepare your sides in advance and reheat later.

Creamed spinach is comfort food at its very finest. It goes with almost anything, or on its own if you fancy. Hattie and I have even eaten it while sitting with our spoons and a bowl full of thick, green unctuousness in front of the television. The nutmeg is key.

To me chips are by definition thick-cut potatoes that have been fried with copious amounts of salt and vinegar. Not quite as thin as American-style fries, not quite wedges. They’re something in between, and they are perfect. Served with a side of tangy, bitter salsa verde, they’re elevated to levels unknown.

/> And then the steak. Rib eye steak has gained so much popularity over the last few years that it’s become as expensive as (if not more than) short loin steak. Seek out a good butcher, though, and you’ll be well rewarded. A reminder of what to look for when buying steak:

Rib eye steak should be marbled, with a large eye of creamy fat in the center. The marbling should extend outward between the three connecting muscles, thin white veins that will keep your steak moist as you cook. The amount of fat might seem unnecessary, but you’re paying for flavor and that fat will render. If you’re looking for leaner, you want short loin or tenderloin.

Breeds aren’t necessarily the key to finding a good steak; it’s all in the rearing. You want slow-matured, grass-fed, native, or rare breed. If you can’t find that, find another butcher.

Dry-aging isn’t for everyone, but it’s something you must try for the full experience. Source a butcher that dry-ages in house. The flavor will intensify and the steak will be more tender and taste the way beef used to.

Thin steaks are pointless unless you’re making a sandwich. At the very least, the cut should be an inch thick to ensure an even, steady cook with a beautiful crust yet a juicy inside.

If you can master all that, you’re on the path to a fantastic steak experience.

YOU’LL NEED

SALSA VERDE

3 cloves garlic, minced

1 teaspoon Dijon or whole-grain mustard, depending on your preference

8 anchovy fillets, chopped

3 tablespoons capers

A large handful of chopped parsley leaves

A drizzle of lemon juice

A good glug of good olive oil

Sea salt and freshly cracked black pepper

CREAMED SPINACH

A good chunk of butter

1 red onion, very finely chopped

1 clove garlic, minced

1 pound (450 grams) spinach

All-purpose flour

⅔ cup (150 ml) whole milk

⅔ cup (150 ml) heavy cream

Sea salt and cracked black pepper

Whole nutmeg

A pinch of ground cinnamon

STEAK AND CHIPS

2 (12- to 14-ounce/350- to 400-gram) rib eye steaks, at least 1 inch thick

5 large starchy potatoes, peeled and cut into large rectangular batons

10 ounces (300 grams) pure duck or goose fat

Olive oil

Coarse sea salt

All-purpose flour

TO MAKE THE SALSA VERDE

Blitz the garlic, mustard, anchovy fillets, capers, parsley, and lemon juice in a food processor. Drizzle in the oil and blitz very lightly to incorporate. Season with salt and pepper and set aside for later.

TO MAKE THE CREAMED SPINACH

Melt the butter in a large frying pan over a medium heat, add the onion and garlic, and cook until softened—this should take 5 minutes or so. Meanwhile, place the spinach into a colander and pour boiling water over it until all the leaves are wilted. Cool the spinach, then pat it dry with a kitchen towel and finely chop it.

Turn down the heat and add a good sprinkle of flour until the onions and garlic have a light covering all over. Add the milk and stir until you have a thickened sauce.

Turn up the heat very slightly and stir in the chopped spinach. Add the cream, bring to a simmer, and simmer until it has thickened further—this takes around 1 minute. If it’s too watery, add a little more flour.

Season with salt and copious amounts of black pepper, grate the nutmeg over it, and add a pinch of cinnamon. Set aside in an ovenproof dish to reheat later.

TO MAKE THE STEAK AND CHIPS

Two hours before you’re due to cook the steaks, take them out of the refrigerator and allow them to come to room temperature.

Preheat the oven to 390°F (200°C).

Bring a large pot of water to a boil. Add the potatoes and cook them until they’re almost soft—not quite, though! You should be able to stick a knife through them with some resistance—normally this will take 7 to 8 minutes, but be careful not to cook for longer. Drain and set aside.

While the potatoes are cooking, add the duck fat to a rimmed baking sheet. Place the sheet into the oven and heat the fat until it’s scalding.

Turn to the steaks. Heat a large frying pan over medium-high heat. Rub a small amount of oil onto the surface of each piece, then sprinkle a good covering of coarse sea salt on top.

Add the steaks to the pan and turn them every 30 seconds or so. Do not add oil—you won’t need it. For medium rare, go for 4 minutes each side.

As the steaks are cooking, add flour to the drained potatoes. Shake them within the colander until they’re covered—this will help to get the crispy coating on the outside. Then, being very careful, pull the rendered hot duck fat from the oven and place the chips inside. They will spit, so be aware! Shake the pan so that the fat covers the chips and place it back into the oven along with the creamed spinach. Decrease the oven temperature and cook for 15 minutes.

As the steaks cook, push the eye of fat down into the pan to help it render. After the 4 minutes (or 5 to 6 if you’re looking for medium), remove the steaks from the pan and place them on a plate or board. Immediately cover them with foil and a kitchen towel and allow them to rest for 10 minutes.

Remove the creamed spinach and the chips from the oven—they should now be golden brown and crisp. Using a slotted spoon, remove the chips from what’s left of the fat and dry them slightly on paper towels. Grate a little extra nutmeg over the creamed spinach.

Slice the steaks, plate them up with the creamed spinach, chips, and salsa verde, and serve.

Six

Several weeks into my new job, Ollie and Will announced that we would host a butchery master class on the rooftop of the department store, and that I was to help coordinate. The class would last for three hours, followed by a demo, with dinner and drinks included. Ollie would talk customers through the best cuts to use to make a beef burger, and then Sean would demonstrate breaking down a forequarter. I would press the burger patties, and Simon would cook them up for the guests. I planned it out minute-by-minute, while Ollie, Will, and Simon prayed for good weather. There were thirty spots in the class, and we initially tried to sell tickets on our website with the promise of a free meal and drink at the end, but after an initial lack of interest we had to resort to giving the tickets away in contests on popular food websites in exchange for free exposure. Still, Ollie, Will, and Simon were optimistic. The problem simply lay with our name recognition, they said—we weren’t quite big enough yet to draw a crowd.

Although a detailed itinerary had been sent around beforehand, it went straight to everyone’s trash folder, and on the night, no one knew whose responsibility it was to do anything. At the last minute, Will couldn’t make it, so it was up to Ollie and Simon (who had been miked up by the contracted sound and lighting team that the store’s PR girls had brought in) and me to figure out what was going to happen and when. What transpired involved the three of us sitting around one of the large rooftop tables before the night began, taking full advantage of the open bar to try to calm our nerves. We progressed from beer to bourbon, to bourbon chased with beer, to gin and tonics, and then shots of God knows what, all before the guests arrived. An hour and a half before the event was due to start, nothing was prepared, and we were all horribly drunk. A mad panic set in as we all flew around the decking trying to figure out what still needed to be done.

That afternoon I’d bought myself a pretty black dress to wear to the event and paired it with my favorite black boots. The dress had cost fifty pounds, or five hours of work to me then. I’d accepted a pay cut to take the job, so desperate had I been to escape the Ginger Pig and being stuck behind the counter, so every bit of money I spent had to be accounted for. But after we’d finished our drinks, I found myself standing in the staff kitchen with an apron over my dress, slicing vegetables with Simon looking over my shoulder. Every so often, he took the

onion from my hand and said, “Thinner,” demonstrating with the knife, which was incredibly sharp. A few times, in my drunken stupor, I almost sliced a finger clean off. Once the demonstration commenced and we got through our initial lack of organization, the event itself went reasonably well thanks primarily to the open bar. Our guests seemed to enjoy the burgers as well, and once people got food down their necks, none of the talking seemed to matter anymore. Ollie even told me at the end that I’d done a good job. It was what happened afterward as we all rode back together in a taxi that marked a turning point.

Short ribs were what started it—that small cut of meat right around the belly of the heifer, probably weighing no more than four kilos. A customer who was a keen barbecue cook and clearly eager to demonstrate his knowledge had sent us an email earlier that day complaining about the ribs he’d received in an online order. His complaint seemed pretty minimal: there wasn’t enough fat on the ribs. I’d responded apologetically, offering him a refund, only this customer absolutely did not want a refund. He responded by saying that he had only emailed to let us know that the quality of our meat should be questioned.

There was a heated discussion in the taxi about how we should handle his second email about the quality of the meat. Insults were thrown around: this idiot clearly didn’t know what he was talking about because every cow is different and you can’t guarantee consistency. Our consensus, some twenty drunken minutes later, was that our suppliers were wonderful and this guy was a dickhead. Ollie dictated an email response to me. I was to explain to this customer that we would replace his short ribs with another lot from the same batch, and that the animals we sourced from couldn’t be better. I made a mental note to put the plan into action and send out the email and the new short ribs the next day.

Girl on the Block

Girl on the Block