- Home

- Jessica Wragg

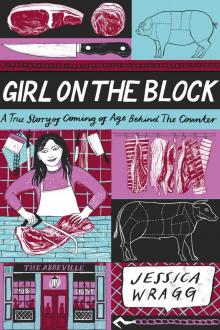

Girl on the Block Page 17

Girl on the Block Read online

Page 17

Ollie, Will, and Simon were committed to selling only rare and native breeds in both the north London shop and the department store. In north London, each cut in the marble counter bore a small handwritten tag with both a price and a breed. We rewrote these tags every day, depending on what we were told was coming in or what sort of aged beef was being brought up for boning before the shop opened. Ollie had suppliers in the hundreds around the UK that would provide us with some incredible beef in small batches, and we had developed a schedule with our suppliers that meant every week there would be a new breed.

Or so it seemed. As with every butcher shop, I suppose, on occasion a customer would come in looking for a particular breed, perhaps being a bit difficult or know-it-all, and we would give them something totally different. Sometimes we had no idea of the breed of a cut of meat at all. Take the ribs we sold, for instance. Like most shops, we went through forty or fifty beef ribs a week for rib eye steak, and that’s twenty animals. Since rare breeds are, well, rare, we were forced to share the good stuff with other butchers around the country and our product couldn’t all be the “hot” breeds like Hereford or Belted Galloway. We got in a lot of Charolais ribs, which came from huge cattle that were bred in Britain but originated in mainland Europe. Because of their sheer size, they were bred commercially and got a bad rep. Often we’d sell them as Angus, knowing that the people who really understood meat would know by sight that the Charolais ribs were leaner and larger. We could spot any such discerning customer a mile off and would steer them toward something that was truly rare breed.

Our customers went crazy for Dexter beef, and for good reason. This tiny, wooly little breed of cattle produced incredibly nutty-flavored fat in very small quantities. I was part of the craze; since the first steak I’d had from Ollie and Simon a year ago, I’d been waiting for another steak that could live up to that experience. In truth, thanks to similar rearing, in many cases Dexter steak was no better than Charolais, but it was the name that people went for. Countless times I’ve seen a crossbreed rib eye sold as a Dexter to an excited yet clueless carnivore, and it’s likely that no one ever knew the difference.

The real issues came with the boxed beef that we would buy from our wholesalers. In butchery, unless you don’t intend on selling much at all, it’s almost impossible to identify the breeds of sub-primal cuts like bavette, flat iron, and short ribs. On each body of beef, there are two of each cut, bavette weighing around 3½ to 4½ pounds (1.5 to 2 kg), and flat iron around 1½ pounds (700 grams). These cuts are sold in such great quantities that a butchery will normally buy them in large boxes of twenty or more kilos cut from hundreds of different animals. It’s unrealistic for us to know the breed of every cut, only that it came from a supplier we trust and have vetted for obvious reasons. Yet it’s difficult to explain this to a customer who comes in with something specific in mind. Once again, by pure consumer demand, we’re creating our own problem: meat eaters who want to know the breed of the piece of meat they’re eating yet still wish to buy it in large quantities and frequently.

Because of how well the shop was doing and the increase in sales volume, we started to see some questionable goings-on. Ollie’s wholesale company began to send us frozen pork ribs from Spain, which we ended up selling as Yorkshire free-range. At Christmas there were rumors of wet-aged Brazilian tenderloins packed into orders for British dry-aged steaks. At one point, we were pointed in the direction of a stall at Smithfield that could help us with a suckling pig. It was sold to the customer as a piglet from Essex, when in fact the stall at Smithfield had bought it from a market in Paris.

Harry was against all of it. He rejected boxes of foreign meat and sent them back to the wholesaler, and if a customer came into the shop asking for something specific and we didn’t have it, he would tell them so and send them away without a sale. It wasn’t a problem, until it was. Ollie got hold of the rejections and the invoices and put them against Harry’s takings.

Somewhere along the way, we got into difficulties with the local food authorities. Ollie had been trying to source Mangalitsa pigs, a rare delicacy that was hugely popular on the Continent and ever more popular among avid UK meat eaters. I never understood why; the pigs, with fluffy, curly hair and short little legs, were extremely fatty. The meat that came off them had a small eye, surrounded by thick, pinkish white fat perhaps two inches thick. A Mangalitsa pork chop might be described by some as “a heart attack waiting to happen.” Nevertheless, we had countless requests for the breed. Ollie managed to find a breeder somewhere up in the Cumbrian region of northwest England who supplied us with a couple of carcasses. To his dismay, the meat barely sold at all, our regular customers being put off by the amount of fat in the meat and only the enthusiasts purchasing a small amount—nowhere near enough to get rid of two whole bodies. We ended up putting a lot of it, even the more expensive cuts, into sausage meat.

Yet once the sausages had gone, the requests still came in by phone and email from those few dedicated followers. I replied to a few of them, apologizing that we didn’t have any Mangalitsa at the moment and that we didn’t expect to have it any time in the near future. Instead of swallowing his pride, Ollie almost always overrode me, chiming in to say that although we might not have any at the moment, he was looking for a new supplier and hoped we’d have some in very soon. A month or so later, he found a breeder that supplied Mangalitsa pigs crossed with a British breed, thus making them much less fatty. He bought in double the carcass amount that we’d bought previously, told me to splash it all over social media as pure Mangalitsa, and we waited. What we didn’t anticipate was a scorned pig breeder from Cumbria calling the local authorities to report that we were advertising crossbred pigs as pure. The breeder knew, of course, exactly where Ollie had purchased the questionable pork, and a few weeks later Ollie received an email from the Food Standards Agency (FSA) requesting a visit to the north London store.

Harry went into meltdown. He knew that the meat we were getting in was being sold under false cover, and he began the lengthy task of tracing every single item we had in stock. We spent a good few days labeling, batch coding, and finally putting a trace number on each rib or loin that we planned to sell in the shop. This was much harder than it might seem. A lot of the beef had been hanging in our fridges for twenty or so days, which meant going back through weeks of paperwork to try to find a batch code. It was the blind leading the blind, attempting to guess the breed of a certain beef rib against an invoice that may or may not have gone along with it. Customers who began seeing our meat correctly labeled as Charolais ribs and Limousin sirloins began to ask where our Shorthorn, Hereford, and Dexters had disappeared to.

The FSA worker who came to visit had clearly kept a keen eye on our Instagram and Twitter, something I’d had in the back of my mind when taking heavily filtered pictures of a nice-looking chop or steak. She arrived in a white lab coat and thick-rimmed glasses, with perfect timing of course, when Harry and Emily were on holiday. After she’d begun to look around, Bartek, the wonderful yet troubled Polish butcher who packed our online orders, and I realized that in Harry’s absence we had neglected to fill out the breed trace sheets that she might want to see during her inspection. While Bart showed her around, I grabbed three giant files from the shelving unit in the office and locked myself in the toilet until all of the batch codes, temperatures, and breed lists were up to date. Using an age-old butcher’s trick, I took two different pens down there with me, so that it at least looked a bit like I had filled them in on different days.

She didn’t want to see the trace sheets, though. She was more concerned with the breeds we were displaying in the counter. How did we know that they were exactly what we said they were? Harry’s tracing had been a little haphazard, so Bart and I tried to talk her through the process at great length, hoping that she might be more interested in our attention to detail than in the questionable system itself. Of course, she wasn’t, and she wanted to know how the breeds had been labeled a

fter they came in from the supplier or slaughterhouse, how we knew the codes, how we could prove it, and so on. She left without giving us a rating or looking at the records, with the promise to revisit in two to three weeks’ time, and true to her word she came back. Harry, after returning from his trip, spent those three weeks manically filling in paperwork, and in the end we passed the inspection.

Ollie, meanwhile, had been occupied with other projects: the yearly meat festival held in the dockyards was approaching, and as part of organizing he had many small dishes to taste from chefs all over London, plus plenty of boozy brunches to attend. We sent him news of the inspection and barely heard a response, and Harry went ballistic. His opinion of Ollie had begun to deteriorate. Like me, he was giving everything he had to a company that was just getting by. We’d been left alone to run things, with Ollie dipping in and out whenever it suited him, and when we really needed him he would disappear and ignore anything that he couldn’t be bothered to deal with. Harry was working thirteen-hour days six days a week. He developed a chest infection that soon turned nasty, he barely ate, lost a stone in weight, and became physically exhausted trying to push the shop forward. His relationship with Emily suffered, too. They argued a lot during working hours and I’m guessing even more so in what little free time they had together at home in the trendy part of North London. Ollie’s sharp tongue hit a nerve with Harry, and the two of them would often argue over email and text.

A couple of months prior, I had asked Ollie for a raise. I’d hoped for at least a pound or one pound fifty more per hour, given how much I felt I was doing for the company. I knew that I was being paid less than Emily, Harry, and Bartek; we’d openly talk about salary, as many of us were disgruntled and frustrated with the demands of the job. Rather staggeringly, Ollie’s response was to offer me a fixed yearly salary that would work out to less than what I was currently being paid by the hour. I declined, quite clearly, and asked for more. He gave his perfectly rehearsed response. He was sorry, but there just wasn’t the money to pay me more. Perhaps when we were making more of a profit we could look into it.

After the fiasco with the food inspector, Harry demanded a raise, threatening to leave if he didn’t get one, and within two weeks his salary had been bumped up by a thousand pounds a year. He also managed to get a raise for Emily, on the logic that she was on her feet all day, while I sat behind a desk “tweeting and writing emails.” This attitude was all too familiar to me: physical work, to butchers, was always worth more. I was left deflated and completely demoralized. Harry knew that my raise had been denied—he had not asked the same for me—and it put a strain on our friendship.

Tensions grew as Ollie put more pressure on Harry and Emily to make a profit now that he’d given them raises. Harry in turn pressured me to try to push sales, and I moved into the office at the shop full-time to help them out. Bartek also began to work late to cover for Harry and Emily, who would saunter off at around five o’clock, indignantly claiming that they had worked their set hours.

Bartek, we had recently learned, was in money trouble. We had regular calls to the shop from payday loan companies looking for him after a late repayment, and we would cover for him, saying that he no longer worked for us. Bartek was obsessed with the cryptocurrency Bitcoin, which didn’t help matters. He sometimes spent his lunch break watching the trading platform to see if and when he could afford to invest and buy some. Over the year or so that I worked with him, I loaned him around two hundred pounds to get by until payday. He was a heavy drinker and often turned up to work an hour or two late reeking of cheap vodka and barely able to walk. Still, running the online business, he worked the hardest and longest hours of any of us, and was paid the least. Ollie believed that he would never betray the company and, it seemed, often exploited his loyalty.

One Saturday in autumn, when Harry, Bart, and I were scheduled to work together, Bart didn’t show up. When I listened to the voicemails left for us on the shop phone from the night before, there was a strange, muffled message from a taxi driver at almost three in the morning. In the message, we could make out Bart’s voice as he got into the taxi, and then the line went dead. Harry and I called Bart’s phone repeatedly, but the line was cut off each time before we even reached his voicemail. We worked the whole day with no news of Bart and didn’t think anything more of it until Harry went down to the safe to count our takings at the close of the day.

Granted, the safe had never locked. It was broken and the door on the front swung open unless you propped it closed with the large stack of flyers that we kept below the counter. We didn’t do the actual banking, but would send the cash takings back to Ollie at his wholesalers, where his team would effectively do our accounting for us. Sometimes the bags of money would go missing in transit, lost in the back of a white refrigerated van, eventually making their way back to us after two or three weeks. Often weeks would go by when we’d forget to send the bags and they would pile up so that the safe door couldn’t be closed at all. None of us ever questioned this system. Perhaps it was our contempt for Ollie that kept us from raising a red flag and getting it fixed.

On this particular day I knew that we hadn’t sent over the cash bags in three weeks. The night before I had noticed a whole stack of white plastic bags in the office filled with notes and change. I left the shop after work and went to meet some friends for drinks, eager to get hammered on my one night off. Fifteen minutes later, while I was at a rest between tube stations, Harry sent me a text:

The cash bags are gone!

And they were. Weeks’ worth of cash had completely disappeared. Bartek, in a phone call to Harry after the discovery, confessed everything: he had taken the money to a casino in East London, hoping to win it back plus more so that he could pay off his loans and pay the shop back all at once. Only he had lost everything after five hours of playing cards and roulette. In the end, he’d gone home in the wee hours, broke and hammered, and was too embarrassed to turn up for work the next day.

When Harry told him the news, Ollie’s reaction was surprising: he apparently was calm and thoughtful rather than livid. There had been whiffs of this kind of behavior before, and Ollie had unwittingly taken on a kind of paternal role with Bart. He knew that the only way to get the money back was to keep Bart working, taking a large percentage of each of Bart’s paychecks to put toward the debt he’d accrued. No one really knew what the total sum was, but we did know that it left Bart with around four hundred pounds per month to live on including rent and bills and travel from pretty far east toward Essex.

Before long, Bart had nearly repaid his debt, and we were all relieved. His happy demeanor returned, and instead of going straight home, he started to come out for a drink with us after work on Fridays and Saturdays. The cloud that had seemingly hung over him for the past few months was lifting and he no longer smelled perpetually of vodka. And then, with one more month’s pay left to give, he did the exact same thing again: ten cash bags (probably our own fault for leaving so many in the still-broken safe) were gone overnight, with no sign of Bartek for four days.

Still, he carried on working for us, only this time, Bart was moved to the wholesale operation out east to work closer to Ollie without access to any kind of cash. He returned to the shop at Christmas to help us with the rush after one of our butchers who was dealing with a fairly serious lung complaint thanks to years of heavy smoking stopped turning up. When we finally closed up shop on Christmas Eve, we discovered two bottles of Laurent-Perrier rosé that one of Ollie’s wholesaler friends at Smithfield Market had left with us to give to him. We cracked them open, and thanks to our exhaustion and the lack of food in our stomachs, we were completely smashed in fifteen minutes. That was the last time I saw Bart, and I often think of him and wonder what he’s up to now.

By the following spring, we were all taking work a lot less seriously. The new website had finally launched, one year behind schedule, and my days were suddenly a lot less full. I was “working” from home a l

ot, which meant hanging out with Hattie in her beautiful Clapham flat and answering emails as needed, while she did the same. Harry and Emily, for their part, were resigned to the fact that no matter how hard they worked, they would never really achieve anything as a result of what I think they saw as too many restrictions placed upon them by Ollie. Working days became much more fun, mostly because we had all stopped caring. When I was based in the shop, I’d ignore emails for much of my workday and drop onto the counter to cut for a little while. It was always the best part of my day.

Harry had been in the trade for almost his entire life, beginning as a boy in a family business and working his way up. He and I had a lot in common, as young butchers who’d both had to earn our knowledge, coming up in an industry that was going through a lot of change. His style was a mix of old school—traditional, British names for cuts and methods—and a newer, “foodie” approach. He was also building a platform for himself on social media and had an impressive Instagram following. His fans would go wild for short videos of him creating some mad, artisanal product he would get Emily or me to film. He taught me a lot, and though sometimes it was off-putting, he would watch my work and stop me halfway through to demonstrate some new way of doing something. His way was almost always faster and easier and always ended with a neater, prettier end product.

Girl on the Block

Girl on the Block