- Home

- Jessica Wragg

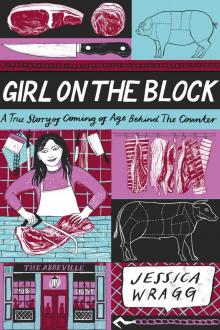

Girl on the Block Page 5

Girl on the Block Read online

Page 5

That was the end of it. I hoped desperately that she might mention it when we found ourselves alone together in the cold room, but nothing. They both smiled at me cheerily for the rest of the day, like nothing unusual had happened, there was nothing to discuss. We all behaved as if it was a normal day, knowing perfectly well that there was nothing normal about what had happened.

FOR A WOMAN IN THE MEAT INDUSTRY, FEELING LIKE AN OUTSIDER IS just par for the course. Five years into my career I heard that there were only twenty female butchers working in the UK. But things are shifting. Today I can easily name thirty of us off the top of my head. Globally there are thousands of female butchers who experience prejudice every day because we are women in a trade that has long been male dominated.

This growth in the number of women in butchery hasn’t happened overnight, and I daresay it hasn’t been easy. It probably began to happen alongside the rise of ethical eating, of wanting to know what goes into our bodies, and the rise of a food industry that supports independent eateries and stores. This shift presented an opportunity for women, who had long been the curators of recipes and techniques in home kitchens, to enter the food industry and to work with food in a way that reflected their passions. The trend began with a growing number of female chefs taking charge in restaurant kitchens and spread to women farmers and then butchers. Women in the food industry who wanted to learn all aspects of their trade saw butchery as part of that, and so here we are.

Articles have sprung up across the internet and through mainstream outlets like the Food Network citing female empowerment in the meat industry. Charlotte Harbottle, owner of Charlotte’s Butchery in Newcastle, UK, is the original self-proclaimed “Girl Butcher.” Cara Nicoletti, another example, is a fourth-generation butcher raised in her grandfather’s meat shop in New York. Both have avid social media followings and have gained some fame in their circles. The most prolific and well-known of female butchers has to be April Bloomfield, who opened two meat-focused Michelin-starred restaurants, the Breslin and the Spotted Pig, along with the female-fronted butchery White Gold in New York City. In a surprising yet perfectly illustrative twist of fate, Bloomfield got caught up in scandal after her business partner Ken Friedman was accused of sexual misconduct in the restaurants they owned together. Bloomfield has been widely criticized for standing by Friedman rather than supporting her female employees, though in interviews she claims that she only did so because she felt that he held all of the power in their partnership. There have been mixed opinions about the way Bloomfield handled it all, but to me, if you are an empowered woman building a career, you should be prepared to defend the women who work for you, even if it means sacrifice.

The few of us who have managed to gain recognition for our craft are doing damn well at it. We are still the surprise, still the minority, still put into a niche category in an industry that in the US alone is worth ninety-three billion dollars a year. Being a woman in butchery has its pros and cons, that’s for sure. The way I see it, we tend to have a steadier and more methodical approach to a carcass, and we tend to respect the life of an animal when considering it for meat. Back in the mid-twentieth century, when the industry was fully male dominated, traditional butchery meant large pieces of meat for sale and a strict number of cuts categorized by the way that they should be cooked. Nowadays chefs, foodies, and consumers are looking for more than just a chuck roast. The rising number of styles of cuisine that the average customer wants to master has meant that every butcher must keep up with trends and take a more artisanal approach, finding new cuts on a carcass and new ways to cut and trim meat.

Fifty years ago, your choices in a steakhouse or butcher shop were limited to round, tenderloin, sirloin, short loin, or rib eye steak. Now there are more than twice as many different cuts on the menu. Onglet, the diaphragm muscle, is cheap and known for its strong flavor. Flat iron steak is from the central chuck, great for flash frying with a beautiful marbling. Bavette steak, which gained popularity in France, is a flank steak and works great when pan-fried to medium rare. Tri-tip, from the bottom sirloin, should be grilled quickly and served whole. Butchery is no longer about large, rough cuts. It’s an art form, and the more that it is viewed as such, the more women will enter the industry looking for a career.

As much as butchery is evolving, it is and always will be a hard job. It’s dirty, it’s disgusting, and it’s physical. It involves working in the cold every day, dealing with dead bodies, and coming home at night to find dried blood on the back of your jeans. It requires lifting up to fifty kilos at a time, wearing your hair up every goddamned day, and long hours. It is in no way glamorous. It’s not a career choice that allows you to wear what you want or to meet friends for a drink after work without having to worry about blood beneath your nails.

Female butchers endure a lot of shit. Customers often overlook us behind the counter in favor of our male colleagues. Sexual harassment, both verbal and physical, is rife in large meat processing plants and small butcheries alike. Men will typically get preferential treatment for a job opening. Chefs will call you sweetheart with a patronizing tone on the phone. But sticking with it is rewarding, because at some point, between learning about carcass balance, slaughtering, and procurement, it becomes easy to fall in love with this job.

A WEEK AFTER THE CHICKEN LIVERS INCIDENT, HARRIS CORNERED ME in the fridge to apologize. It was Saturday and I’d just arrived at work ready to start my day. I was picking up chicken from a shelf in the fridge when the door shut behind me, plunging us into yellow light from the lamp above. This was our first encounter since, and though it was hard to avoid someone in that place—glass everywhere, open plan—I had been doing my very best.

“Listen, Jess . . .”

I turned around to face him, embarrassed and afraid of what was coming. I wanted desperately to forget about the whole thing, having spent the week thinking about how and if I could have avoided it in the first place. There had been times when I’d allowed Harris to hug me, when I’d laughed at his jokes. I’d racked my brain trying to figure out if I had flirted back, had given him the wrong idea at any point over the last two and a half months.

He had a pained look on his face, as though he was truly sorry about what had happened, which made me cringe even more.

“I got pulled into the office with Laura this week. She reported the incident to HR the day after. They made me talk through what I thought had happened and then she gave her side. It was all a bit of a mess,” Harris said, and he fiddled with the corner of his worn apron. “I just wanted to say how sorry I am for last week. It was all a bit of fun that got taken too far.”

“Oh, it’s fine,” I said. “It’s fine, really, it’s fine.”

“No,” he said, “it’s not fine. I’m really very sorry and it won’t happen again.” But in spite of his apology, I remained trapped in the fridge, his wide frame spanning the full width of the door. His arms rested on the metal trolleys on either side of him, gripping at the shelves, and I noticed that his knuckles were almost white.

I didn’t doubt his sincerity in that moment, but I just wanted it to be over. My shoulders shrunk inward and I bent my knees in an effort to disappear.

“It’s alright.”

He lunged forward and pulled me into a hug with those big arms. His head, heavy, rested on my shoulder, and through my overcoat he stroked my back.

I wriggled free seconds later.

“Okay, well, thank you for your apology,” I said, and ducked beneath his arm and out into the butchery again.

Laura was standing outside the fridge waiting for us both, and she shot me a look. I smiled back meekly. Amy, who had missed the chicken livers incident, was also there that day. Someone, quite probably Sharon, had filled her in. She muttered, “What was that?”

Amy, though also sixteen, was wiser than I was. From what I knew, her parents had gone through some serious issues over the span of her lifetime, and it had only served to make her a harsher judge of character

and less forgiving. She talked constantly about feminism and sexism and racism and homophobia, about the injustices of the world, in a way that was over my head. Sometimes she would say something that seemed so profound that I figured she must have stolen it from a textbook or a great novel. In hushed voices we huddled in the corner by the freezer, as far away as we could get from the fridge.

“He apologized,” I whispered.

“You don’t look happy about it.”

“It was fine, apart from that he did it in the fridge, and then he hugged me at the end.”

“Oh fucking hell. Apologizing for sexual harassment by acting completely inappropriately in the workplace yet again.”

“I’d rather he’d have just not said anything,” I said.

“I know, but at least he knows what he did was wrong. People who are unaware of their flaws can never fix them,” Amy concluded.

Over the next few weeks, Harris steered clear of me. My lunch breaks were peaceful, and I started to believe that things had changed. The other butchers began to show me things—how to tie string, how to properly cut steak. Whether it was out of sympathy or some innate gratitude for taking Harris down a peg or two, they seemed to have decided that I was worth their time.

Christmas passed, and when we all returned in January, I discovered through my chats with Adam that almost everyone in the shop hated Harris. They despised his crude manners and the way that he would undermine authority. The girls who worked in the restaurant attached to the farm shop also hated him; they were well-known to be pretty, and of course they became the objects of his unwanted attention. I had noticed that he made excuses to go over there and say inappropriate things to them at lunch.

With Adam on my side, and knowing that I wasn’t the only one dealing with Harris’s harassment, I vowed to be tougher. The next time Harris inevitably cornered me was around Easter.

“Your half term is coming up soon, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Well, it’s my boy’s half term, too,” he said, referring to his eight-year-old son from his first marriage. “I thought we could go away somewhere.”

In disbelief, I laughed out loud and I laughed hard. I was so positive that he was joking that I entertained him for a moment.

Still giggling, I replied, “Yeah, alright.”

Without a beat, he said, “Where do you fancy going?”

I looked him in the eyes, and it became clear that this was not a joke.

“We could take the caravan up to the Lake District. Me, you, and the boy, it could be nice.”

“I’m busy at half term,” I said, and walked away. The conversation was done.

To this day it’s still one of the most bizarre exchanges of my life. I worked a few days over half term and Harris, true to his word, took a caravan up to the Lake District with his son. I had thought he was joking. But he wasn’t. He was deadly serious. When I told Amy about the conversation, she howled with laughter before a frown quickly passed over her face. Adam made a groaning noise, like he was going to throw up. Sharon vowed to chop off his balls.

I never reported Harris’s behavior to management myself, which might seem unbelievable considering all that I’d been through. But at sixteen I was terrified of risking the opportunity I’d been given, and I knew that a man, twenty-six years my senior, who had been with the company for five years, would always be believed over a child. Women should never put up with predatory men—I know that now. But this was a lesson that came with age and experience.

In my final year at the farm shop, another female employee, around my age and a friend, had a boob job. John, a relatively new butcher in his early fifties with a stomach that protruded a foot over his belt, began to message her on Facebook. At first it seemed innocent, but three months later, no one in the butchery would speak to her. She showed me the string of messages. John, married for twenty years, had pursued her relentlessly, telling her that he couldn’t live without her, that seeing her every day was the only thing keeping him at his job, that he thought about her every single minute. When she had asked him to stop before she filed a report, he went to the other butchers and told them that she was trying to ruin his career. In the end, she did report him, but all that happened was that she was moved to another department. He kept his job.

And what became of Harris? I know that he is still working at the farm shop to this day. His girlfriend works in the restaurant. She is seventeen years his junior.

Know Your Knives

Rule number one of kitchen knives: a dull knife can be much more dangerous than a sharp one. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve found myself stuck in my parents’ kitchen, trying to chop onions or mince garlic with knives that haven’t been sharpened since the late nineties. Sharp blades are accurate. Used correctly on a piece of meat or a vegetable, there is very little chance of a sharp blade slipping. Dull blades, however, with their larger surface area, won’t make a cut but will slide instead, meaning there’s much more chance of you losing a finger.

Knife-sharpening steels are easy to come by in cookware shops—look for a steel that’s made of material closest to that of your knife, as anything that’s too rough can tend to over-sharpen, making the blade uneven after a while. If you find yourself in a situation with a dull knife and no steel but you have another knife from the same set, use the back of it to sharpen your dull knife. Don’t make the mistake of putting too much pressure into sharpening. The idea is to glide the blade at roughly a twenty-degree angle on the steel from blade to tip. Do this four times on each side, alternating sides of your knife blade, and you’ll see an improvement.

Butcher’s knives are similar to kitchen knives, but whereas chef’s knives and kitchen knives are made from thick, sturdy steel, butcher’s knives tend to be a little more flexible. These are the knives that any good butcher will have in her arsenal:

BONING KNIFE These knives can have either a straight or curved blade. Straight boning knives are good for removing larger pieces of meat from the bone, whereas curved boning knives are better for the fiddly bits and have a little more give in the metal.

STEAK KNIFE With a blade around ten inches in length, these knives are, obviously, used for cutting steaks and slicing larger bits of meat. Again, they come either straight or curved, but I much prefer a steak knife with a curved blade thanks to the extra movement the curve allows.

HANDSAW Handsaws generally come in all different sizes, but the most important thing will be the blade. With the frame shaped like a bow, the blade will be thin with a slight bend but sturdy enough to saw through bone accurately. The actual size of the saw will depend. Some butchers prefer shorter saws so they have more control, and others prefer them longer. I prefer something right in the middle. To me shorter saws require more effort, and it’s much easier to get on with a saw that’s got a bit of length so there’s less back and forth.

CLEAVER Used to chop through smaller, more manageable bones in one fell swoop. Accuracy is key, so the cleaver needs to be heavy enough for gravity to help with the movement but not too heavy for the one using it to lose control. The blade will have a much bigger surface area than that of a knife but still will be sharp enough to cut bone.

There are many other types of knives that a butcher might keep in her kitchen, but in my opinion, these essentials are all you really need. If you’re just starting out, Victorinox makes the best, most reliable knives out there that won’t break the bank.

An Ode to the Women of Meat

Beneath a Styrofoam canopy, lit by the false white of the overhead lamps, she considers the animal in front of her. The block, wood worn down in the middle to a curve by years of use, bruised and splintered and toughened in places, wobbles beneath the force of her cleaver. The metal legs on which it stands, rusting in the top corners, gleamed silver a long time ago. Now the steel is matte, almost gray, and over the years has bowed to appear misshapen.

As a child, she wanted to be a veterinarian. She remembers every

night between six and seven a program on television that captivated her—about a kindhearted vet who treated cows and sheep and dogs. She always hid her eyes behind a pillow during the gore of the operating footage.

Is what she is doing now so very different? Her knife is sharp, its blade worn down until it is as thin as a scalpel. In front of her, a middle of pork, two and a half feet long and a foot and a half wide. Ribs exposed, glistening beneath thin silver skin, meat protected on the underside. The skin, with an inch of fat beneath its surface, is tan, the small nipples of the sow still attached. No, it isn’t so different.

On a late night surfing the internet a few months ago, she had read the blog of a food writer who estimated that she is one of only twenty-five female butchers in the UK. She wondered, immediately, who took the time to count them, and set about searching for more on Google and via telephone, cold-calling other butcher shops to see if the voice that answered the phone belonged to a man or woman. After a while she began to believe it; it was accurate enough to her to illustrate how alien she felt in her workplace, a statistic that made her feel special and justified in explaining her love for the trade.

All over the world, women have begun to take hold of the meat industry—others like her are stepping up to the block and shaping their shared craft with a keen eye for animal husbandry, a compassion for welfare, and a palate for new and interesting flavors and varieties of meat.

FEMALE-FRONTED BUTCHERIES AROUND THE WORLD

BAVETTE MEAT & PROVISIONS

Pasadena, California

Run and founded by Melissa Cortina, Bavette is a shop that’s committed to moving away from a grain-fed beef supply in favor of meat that is pasture raised and humanely treated. Cortina discovered butchery after leaving a PhD program to study under a James Beard Award–winning chef. She works with local ranchers, and her store sells a fantastic array of other home-cooked goods, too.

Girl on the Block

Girl on the Block