- Home

- Jessica Wragg

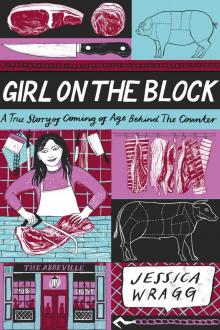

Girl on the Block Page 8

Girl on the Block Read online

Page 8

TAIL The tail is the secret weapon on the carcass. Once skinned, the tail is cut through the joints into sections, each piece with marrow in its center and a small amount of meat surrounding. Casserole the tail with Carribbean-style flavors for an authentic take on the meat, or braise it in red wine and beef stock before shredding from the bone for a hearty pie filling.

Four

Moving away from Chesterfield at nineteen was an easy decision. At eighteen, I had taken my A-levels in chemistry, physics, and biology and failed each one, the result of having allowed myself to be led by the advice of a boyfriend who thought these subjects were more practical than those I actually loved and cared about: English literature, English language, and history. I ended up having to stick around for an extra year to retake my exams. By 2011, there was barely anyone left in town who I knew. I missed my old friends who were constantly posting pictures on Facebook and Instagram of the new lives they had started, out drinking almost every night of the week with new pals in London and Nottingham and Liverpool. Meanwhile, I lived for Monday nights when I’d go out with the few friends I’d made in the year below me at school. We would dress up and get the last train into Sheffield, the nearest large city, and crowd with a load of other students into a huge, dirty nightclub called Corporation that served quadruple vodka mixers for two pounds fifty. We’d leave the club at around four in the morning, catch the first train back to Chesterfield at six, and roll straight into our morning classes.

I was restless; once I retook my exams in my preferred subjects, I applied to a number of London universities with three A grades under my belt and received three conditional offers from Kingston, Royal Holloway, and Westminster. Westminster was central, the campus just off Oxford Street, and desperate to be in the middle of the bustle, I accepted their offer. I had planned to live with my then boyfriend when I got to university—he had already been living in London for a year—but six months before I was due to move, we broke up. Despite having spent a few weekends visiting him while we were still together, I found the city intimidating. The real London was nothing like what I’d read about in books and seen in movies like Notting Hill and Bridget Jones’s Diary. Real London was packed to the rafters, full of people more interesting than I could ever hope to be.

The summer before my move to London was my last at the farm shop. I was distracted by the move and the job took a back seat. I’d stopped asking to learn, and things had plateaued. The team hadn’t changed, and I could no longer trick the new starting butchers into teaching me things. The old guys were as reserved as ever about sharing their knowledge and their secrets. When I sensed that the butchers needed a hand, I would swoop in to roll or tie a roasting cut or French trim a rack of lamb, but the first carcass I broke was my last there, and that’s where my learning curve ended.

A few times a year, when I find myself back in Derbyshire with a few hours to spare, I’ll make the drive over the rolling moors and twisting hills, through the country estate and past the herds of sheep and roe deer to the shop. The faces are still mostly the same, except for Steve, who took early retirement and bought a caravan in the Welsh countryside. My visits don’t cause much of a stir—their novelty has worn off. Harris never comes to the front to say hello when I stop by. Something tells me that he understands what he did. Richie and Ian still take a vested interest in how I’m doing. When I visit, they’re the first two to greet me and the last two to say goodbye. They recognize, somehow, that they were instrumental in starting me off on this path, and that my gratitude is with them. Throughout my final months at the shop, they were the only reason I went in to work, and they’re the reason I am where I’ve ended up today.

In the September after my nineteenth birthday, my London adventure began, and it was a rough landing. In high school, I’d been top in my class, head girl, I had the lead in musicals, and was first pick for most extracurriculars. At university, none of that mattered. There was always someone louder, more intelligent, prettier, funnier. It was difficult to find my place, and I suddenly realized what a small-town girl I was. I moved in to the nineteenth floor of a residence hall in Marylebone, opposite Madame Tussauds, close to Baker Street station in the heart of the North-West. It was a neighborhood that wasn’t really meant to be lived in—a tourist trap with a statue of Sherlock Holmes right outside the underground station and a museum at 221b Baker Street that mocked up the sleuth’s house to a tee. The area was full of small supermarkets and restaurants and very little else. But my hall was the closest to campus, and in my mind, that was hugely important as I didn’t know the city well. I ended up with a room in a corridor full of foreign students who were on a three-month exchange program. When their time was done, they all left.

My one friend in Marylebone was Anthony. He was tall, a little paunchy, and chronically wore black skinny jeans and a varying band tee. He had a slight West Country accent, and his jokes were always bordering on inappropriate. We first met on move-in day, after my parents had left. I’d propped open my door with a crate of Strongbow cider and heard movement next door, some shuffling of boxes and the dragging of a suitcase, before music started blasting. It was a song by the Arctic Monkeys, a band I’d grown up with that hailed from the next city over, and I walked over to introduce myself. That first night we joined a group of other first-time Londoners and went to an overly fancy, typically expensive club in Leicester Square. Inseparable all night, we walked home arm in arm, and once back in our characterless communal kitchen on floor nineteen, we cooked our first ever drunken meal. Anthony went to his cupboard, pulled out a large, round, flat tin, and opened it with zeal. After thirty minutes in the oven, the tin came out, and he handed me a fork.

I still remember the taste of the tinned supermarket pie; Fray Bentos chicken and ham, I think. The crust, which in his drunken state Anthony had managed to burn within an inch of its life, was still barely crispy, and the underside of it was soggy and sticky with the fat that had come off the chicken while cooking. Still, after ten gin and tonics, I devoured it. The chicken was soft, some lumps of gristle throughout the flaky meat, and the sauce tasted of nothing but cheap butter and cream with a little pepper. It was the kind of food that only makes sense when drunk (and probably to no one outside of the UK), but for the first time in what seemed like such a long time, I was enjoying cheap meat and, quite clearly, wasn’t having a second thought about it.

We wolfed it down, breathing quickly through open mouths to try to cool down the piping hot filling, scraped the outsides of the tin, and ran our fingers around the rim to ensure we got all of the sauce. I vaguely remember Anthony licking the webbing between his thumb and index finger where some of the grease had dripped.

I lived the stereotypical student’s life that year. It seemed useless to spend money on anything decent to eat when we had booze, nights out, and pub crawls to spend on instead. I might have eaten one piece of meat that wasn’t from a supermarket or a takeaway that year, and that was when I was feeling particularly frivolous and took a trip down to Selfridges in between my classes to buy a steak. I don’t remember what it was like. Like most students my age, the year was a drunken haze only interrupted by essays, exams, and seminar group meetings.

Although Anthony and I were officially Marylebone residents for that first year, we spent most of our time in Lambeth Halls, over the river to the south, where our friends Hattie, Chloe, and Jamie lived. I would stay over there four or five nights a week, returning to Marylebone when there was a party or when I needed a fresh change of knickers. In second year, Chloe, Anthony, and I joined forces, and after a lot of searching, found a flat in an ex-council building close to the Elephant & Castle underground station.

The flat itself, looking back, was atrocious. Uneven floorboards, a kitchen that more than one person could barely fit inside, small rooms with budget furniture, and unfriendly neighbors. We thought it was a palace, until five days into living there when I came home to find all of our belongings gone and the place ransacked by b

urglars. From then on, neither Chloe nor I could be at home alone, and we hated the place. Highlights from that year include:

Having to call the police after our upstairs neighbor hit his girlfriend.

Hosing down my windowsill after the same upstairs neighbor vomited out of his window.

Shaking off two men who followed me home one November evening.

Finding a man shooting up drugs in our stairwell.

Putting up with our creepy neighbors who stood on the balcony outside our window whenever they were on the phone or whenever they heard us leaving the flat.

Receiving a lecture from my mother when I went home for a visit because my clothes reeked of cigarettes, as we had all, rather carelessly, started to smoke indoors.

The only real upside to that place, looking back, was that we discovered Borough Market.

Although our flat seemed out of the way, we were only a ten-minute walk from the South Bank, where the market made its home. American friends we’d made in our foreign exchange residence had been there to snap their obligatory photos eating fresh oysters and humungous sausage rolls. Pictures of rabbits and hares with the fur hanging from rails above one of the butchery stalls. We’d never been because it didn’t seem like it was our thing. To us, the market was for tourists wanting perfectly coiffed cappuccinos or for thirsty bankers after work, standing outside in the sunshine drinking pints of Guinness and discussing the big deals that they’d made that day. It never occurred to me, until we actually visited, that this place might be utter heaven.

One Saturday a couple of months into our tenancy, Anthony and I wandered down to see what all the fuss was about. We found crowds weaving in and out of stalls beneath a huge metal awning in a space that was perhaps the size of a football field. There were groups of tourists, men drinking outside the pubs that lined the main street into the market, queues winding around the corner for restaurants I’d never heard of, men and women with cotton tote bags full of bread and cheese and meat performing their weekly shop. The ornate green painted metalwork of the market stalls beneath the greenhouse ceiling made them look like they were from a different era. In addition to the bakery stalls and fishmongers I’d expected to see, there were spice merchants, artisan cheese sellers, organic greengrocers, and charcutiers in huge numbers. I’d taken twenty pounds out of the bank but ended up spending sixty. On my student budget, that was a fortune.

We bought pecan brownies from a small stall out back, had vegetable samosas made with filo crispier and lighter than I thought possible. We sipped watermelon juice and watched couples shopping for dinner parties buying whole legs of Spanish hams. From a fishmonger with a counter that was twenty feet long and filled with live lobsters, we bought a bag of crab claws, which we later cracked and tore apart with our bare hands over our tiny dining room table. When Chloe came home from work that day, she complained about the fishy stench, picking shell from the floor of the living room, but Anthony and I were elated.

It became a bit of a tradition then, waking up late on Saturday morning, walking down to London Bridge, stopping off for a coffee and a pastry from the Italian deli on the way, and then buying crab and brownies from the market. I lived for it. I’d found my favorite place in London. Whenever drinks were suggested, I managed to steer our friends toward the market. If someone wanted lunch, I’d propose we meet at one of the restaurants there that I’d researched extensively after the first visit.

It wasn’t until our fourth or fifth trip that I noticed the huge, bustling butcher shop on the perimeter of the market. Anthony and I went inside to have a look at the counter. There was so much meat packed inside that I could barely take it all in. On one side, rows of sixteen different types of sausages, which I could tell were handmade because of the slight difference in their sizes. Bacon and pork next, in large, intimidating pieces, and beef in black trays piled high. On top of the glass, the butchers had placed ribs with what I understood to be good marbling and tickets with prices I couldn’t comprehend. They had seven or eight different varieties of chicken, French veal, lamb, goat, and game in the fridges to the right. Through the glass counter, covered with fingerprints, I pointed at the black pudding nestled in between the smoked hams and hocks without any real intention of ordering. A burly Eastern European butcher cut two slices for me without asking, put it on the scale, and stared over. I was so transfixed by his confidence that I started asking for more things I didn’t need. Behind him, his colleagues were running back and forth, steadying themselves by holding their colleagues’ shoulders or hips, climbing over each other to see who was next in line. Someone was transferring sausage rolls from an industrial oven to a hot hold, another butcher, older and frail, was standing on a stepstool so that he could reach the block on which he was breaking down beef. They were all men, all laughing, shouting, or fighting to be the center of attention.

In the end, I walked away with the black pudding, a strange dark sausage that Anthony devoured in seconds flat, and two steaks that I forgot about in the fridge and eventually went moldy. I didn’t care. I wanted to be part of what I had seen.

“I could do that. Did you know I used to work in a butcher’s?” I asked Anthony as we walked out. I felt tingly. Just being in proximity to that familiar environment had excited me beyond belief. Meat was the one thing I knew.

“Yes. You’ve told me . . . a million times.”

I hadn’t realized that I’d even mentioned the farm shop to Anthony. As far as I was aware, I’d kept it a secret from my university friends, worried about the images of bloody animals that it might bring up for them.

I turned and took a picture of the shop and noticed a large, gray wooden pig hanging down above the shuttered doorway.

Across its belly, in gold writing: THE GINGER PIG.

LITTLE DID I KNOW, TIM WILSON, THE GINGER PIG’S OWNER, WAS ONE OF the most respected meat producers in the country. As a mostly inebriated student, my knowledge of London’s food scene was negligible. I couldn’t stop thinking about the shop, and one evening after a night out, I found Tim’s contact information through a quick Google search and sent him an ill-thought-out email. The company secretary, someone named John, wrote back in a “thanks, but no thanks” kind of way. They weren’t hiring, but they would keep me on the books.

Two days later, I heard from them again. Tim would be in London soon, and he wanted to meet me at the Ginger Pig’s Marylebone location to talk through my past work. I scheduled a meeting, but when I began to research the company more thoroughly, any confidence I’d had that I might be qualified for a job there quickly disappeared. Founded in the mid-1990s in Borough Market, by the time of my interview the Ginger Pig had grown to a multimillion-pound food business. I trawled through interviews with Tim in the Times and the Telegraph, watched video clips of him on Countryfile with two familiar TV presenters, and unearthed countless restaurant reviews mentioning the Ginger Pig as their meat supplier. Their website had in-depth blog posts dedicated to farming, procurement, slaughter, and dry-aging, the majority of which I was learning about for the very first time. The amount of information was overwhelming, and after ten minutes of studying the website I decided that there was no way I had a chance at a job here.

Still, I went to meet with Tim in Marylebone. Standing outside of the shop, I could see my towering residence hall from first year of university peeping over the town houses two streets over. I knew the area well with its indie bookshops and artisanal bakeries and a new string of high-end fashion boutiques that had popped up just before I’d left the year before.

The day was hot and muggy, and I’d taken the bus over from the other side of London. Looking back, it’s unclear whether I knew what a job interview actually entailed. I’d chosen a short, flippy leather skirt that almost exposed my arse and a short-sleeve denim shirt tucked in at the waist. Ignoring the heat, I’d also thrown on a thick vintage wax jacket four or five sizes too big that I’d bought a few weeks before from a shop in Camden Market. I had a thing for rings

at the time and wore seven or eight on each hand, along with nail art I’d painted myself the night before.

As I approached, I could see a robust man through the front window, perhaps in his late forties, leaning over the counter. I tried to enter the shop, but the door was locked, and so I pushed and rattled at it until he turned. His face fell slightly at the sight of me, as he reached upward to pull down the lock and swing the door open.

“Jess?”

Tim Wilson wore a thin green sweater that was stretched and worn slightly at the elbows, with a checkered shirt that peeped out around the neckline and loose brown slacks. His shoes, which looked like suede, were covered in a thin layer of dust. He kept one hand in his pocket at all times, using the other to pull the door open for me, to shake my hand, to lean on the top of the glass counter as we spoke. There was a hint of a northern accent, but it was one that I couldn’t quite place. His face was friendly and reddened at the cheeks. He looked like someone who spent a good deal of time outdoors, but also like someone who was in charge.

The way the men behind the counter stopped to speak to him was impressive. He commanded their attention, almost like they were afraid of him, and the others who weren’t involved in that specific conversation would stop and listen, as if they might hear something of importance or feared that the talk might mention them.

It suddenly struck me that I was, in fact, incredibly nervous. As Tim finished a conversation with one of the butchers, my eyes ran slowly over the meat behind the counter. This was a different ball game—the meat was darker and looked somehow less plastic than the bright red cuts at the farm shop. Meat was rolled and tied with garnish; some cuts that I’d heard of, and many that I hadn’t. I cursed my lack of preparation, frantically trying to remember everything I read about on the website from the night before.

Girl on the Block

Girl on the Block